Inspired by our last post, a review of the film The Duke, about Kempton Bunton’s theft of Goya’s painting of The Duke of Wellington from the National Portrait Gallery in 1961, we thought we’d look at Manchester Art Gallery’s own brushes with the law. Had our own gallery been the victim of similar acts of theft and criminal damage?

Manchester Evening News 12th July 1962

Unfortunately, (or fortunately for this post), we didn’t have to look too far. 1913, in fact. On April 3rd that year, a court in London sentenced Emmeline Pankhurst to three years in prison for ‘inciting persons unknown’ to commit the bombing at the unoccupied house of David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer. In response to the sentence, there followed a rash of Suffragette protests or ‘outrages’ across the country, including bombings of railways carriages, setting fire to property, and damaging post in pillar boxes. In Manchester, just before closing time at 9pm on April 3rd, 1913, three women entered the Art Gallery. Having smuggled in small hammers, the women set about smashing the glass on thirteen paintings.

Lillian Forester, Evelyn Manesta and Annie Briggs 1913 (Ref: m08224 Manchester Local Image Collection)

The Manchester Guardian later reported that “an attendant… heard crackings of glass follow each other rapidly. He immediately rushed into the room followed by another attendant, who was nearby… but the women escaped from the room. The attendants, called to the door-keeper, the doors were closed and their retreat cut off.

“The women were quietly kept within closed doors while the Town Hall was informed. The Chief Constable and a superintendent at once went across and took the women to the Town Hall. There they questioned them and, after charging them, allowed them out on bail.”

Captive Andromache (1888) by Frederick Lord Leighton © Manchester City Art Gallery

Among the works that they attacked were The Last Watch of Hero and Captive Andromache by Lord Frederic Leighton (we’ll be coming back to Captive Andromache in a future instalment), Astarte Syriaca by Gabriel Rossetti, The Flood by John Everett Millais, Sibylla Delphica by Edward Burne-Jones, The Last of the Garrison–Briton Riviere and The Shadow of Death by William Holman Hunt. All these paintings are still on display today.

In court, the judge charged the three women, Annie Briggs (48) Housekeeper, Evelyn Manesta (25) Governess and Lillian Forrester (33), married, with unlawfully and maliciously damaging thirteen paintings in the gallery to the cost of £85 for damaged glass and the repair of two canvases at £25. The jury acquitted Annie, who said she was only there to support her friends. The judge sentenced Lillian to three months' imprisonment, and Evelyn to one month.

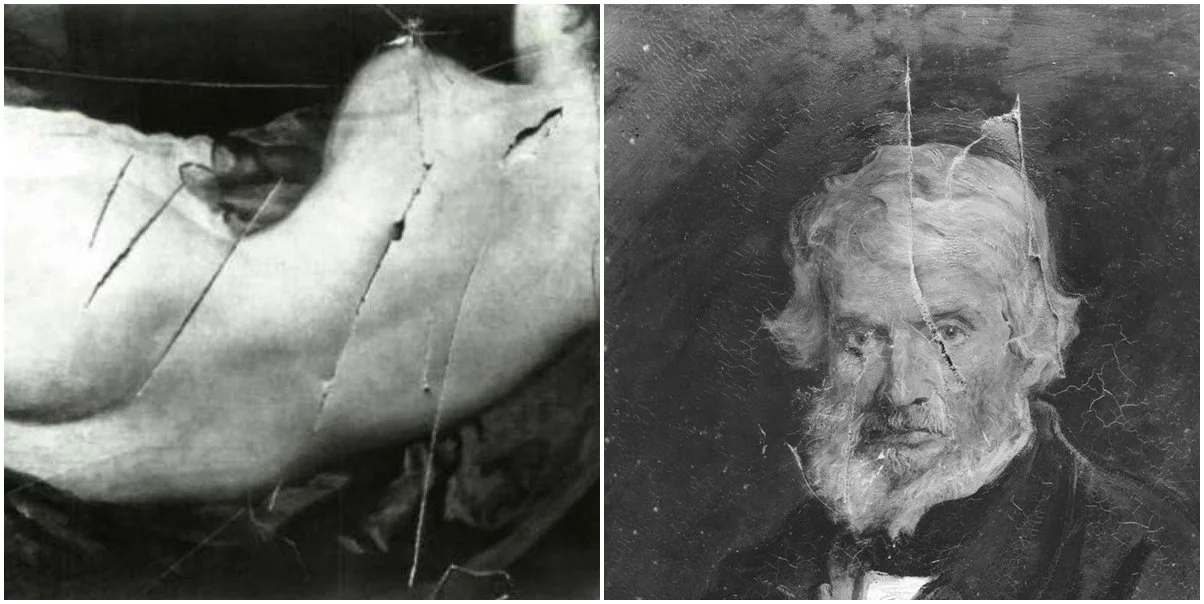

It was the first time in the country that someone had attempted to damage works of art in a political attack. It wouldn’t be the last. In March 1914, suffragette Mary Richardson took a meat cleaver to the Rokeby Venus at the National Gallery. And in July that year, at the National Portrait Gallery, Ann Hunt took another cleaver to Millais’ portrait of Thomas Carlyle, one of the Gallery’s founders.

Damage to (L) The Toilet of Venus (The Rokeby Venus) (1647-51) by Diego Velazquez © National Gallery and (R) Thomas Carlyle (1877) by Sir John Millais © National Portrait Gallery, London

In response to these attacks, some larger galleries took to hiring plainclothes policemen. This was often too expensive and other galleries relied on plain clothes attendants instead. Police advice recommended that visitors left muffs and parcels at the entrances, along with the umbrellas, as some might use them to hide weapons.

Manchester Art Gallery (then known as the City Gallery) wasn’t the only art gallery in Manchester. From 1906 until late in the century, it had six other associated branch galleries around the suburbs; Fletcher Moss, Wythenshawe Hall, Queens Park, Platt Hall, Heaton Park and the Horsfall Museum. These were at risk from crime, too.

And it wasn’t always artwork that the culprits targeted, as Platt Hall found out in 1937 when youths vandalised its public toilets. The offenders were caught and handed over to the police. We covered this incident in an earlier blog post.

Platt Hall © Manchester Art Gallery

A year later, in 1938, it was the City Art Gallery’s turn again, when someone attacked the painting Work by Ford Madox Brown with a brick.

By now, all Gallery Attendants carried police whistles when on duty. The Gallery also swore in most Attendants as Special Constables, giving them the power to detain visitors. It was an economical solution after the Suffragette outrages. Exceptions were those men who were “junior in service i.e. having joined the staff since the last batch were sworn in, or, as in two instances, have physical disabilities, which would render them unsuitable to act as special constables, while not preventing them from carrying out their duties as attendants.”

Work (1852-1865) by Ford Madox Brown © Manchester Art Gallery

The incident took place at about 5.45pm on Monday 29th of August. Work was then on display in ‘Room No.1’ (now Gallery 3). Back then, the Gallery had turnstiles fitted in the doorways from the balcony.

On duty that fateful afternoon were Staff Foreman William Edward Cornthwaite, and Gallery Attendants John Robert Leeming, William Frederick Wedgbury, B. Ward, and H. Brydon. Leeming and Wedgbury were patrolling the galleries and Ward was on the door.

Harry Bent, unemployed of Ancoats, was a regular and usually quiet visitor to the gallery. Earlier that afternoon, two gentlemen saw him muttering to himself, telling an attendant, “That man’s crackers!” but he may have been drunk. He was, apparently, ‘a lodging house type’. Bent left quietly, only to return a short while later, carrying a folded newspaper. As it wasn’t a parcel or bag of any sort, Ward hadn’t asked him to leave it at the umbrella stand. He was unaware that inside the paper was a brick.

Leeming was on the first floor patrolling Rooms 1-5 when he heard the turnstile click.

“I came from an adjoining room towards the turnstile and… saw this man with his arm upraised and immediately saw something leave his hand and crash through a large oil painting entitled ‘Work’. I at once caught hold of the man and blew my whistle for assistance. On the floor underneath this painting was this brick. He said, ‘Take your hands off me. I’ve come in to do what I intended. You’re lucky I’ve not done the Cathedral window in.’ ”

On hearing the whistle, Wedgbury, patrolling Rooms 6-9 ran in to assist, blowing his own whistle to alert Ward on the door. Instructions to the Attendants at the time stated that immediately a whistle is blown they must shut the door. Ward did just that to stop any escape, then blew his whistle on the front steps to attract the attention of a policeman. Leeming and Wedgbury then detained the man before he could cause more damage.

William Cornthwaite, the Staff Foreman, continues the story, “I heard an attendant's police whistle blaring and hurried to Number 1 gallery on the first floor, where I found two attendants detaining a man.” He asked why the man had done it and he said, ‘For the things that have been done to me.’ Later he said, ‘You’re lucky. I intended doing this picture,’ indicating the one entitled ‘The Shadow of Death’. I then telephoned the police and gave him into custody.” And then, as an afterthought, added, “there are no loose bricks in the Gallery.”

Interestingly, Cornthwaite was also present at the Suffragette outrage 25 years earlier.

Extract of transcribed interview with William Cornthwaite © Manchester Art Gallery

Apart from the smashed glass, the damage to Work was minor, thanks to the brick hitting a spar of the stretcher behind the canvas, saving it from more serious harm. Still, the cost of restoration was a princely £23 19s 3d.

Interviewing the men later, the Chairman was peculiarly fixated on the Gallery Attendants’ police whistles, pressing each man as to their use and whereabouts on their person.

Extracts of transcribed interviews with Gallery Attendants Ward, Wedgbury and Bryden concerning their police whistles © Manchester Art Gallery

As touching as the Chairman’s faith was in the mystical properties of the police whistle to ward off wrongdoing, would whistles and Special Constable status be enough to deter art crime at the Gallery in the future?