During the past eighteen months, many people have turned to arts and crafts. Making and sharing art has helped them cope with changes of circumstance during the COVID pandemic.

Over the lockdowns, the artist Grayson Perry encouraged everyone to take part in an open project to create art with Grayson’s Art Club, where art is for everyone, by everyone. Members of the public, inspired by his TV show, responded in personal ways to the unfolding events around them and took part in this community endeavour, creating and sharing art in their thousands. From these shared works, he selected the ones which appeared in the exhibition, and will appear in the Second Season exhibition in Bristol.

Grayson’s Art Club, Manchester Art Gallery (c) Manchester Art Gallery

But what can you do with all your newfound arts and craft skills now that Grayson’s Art Club has moved on?

Luckily, there’s an art movement just for you; one that is all about reaching out, connecting and bringing about a sense of community, which is probably more relevant now than ever.

During a time when social contact was forbidden, reaching out to those you cared about was hard. Oh sure, technology helped; social media, Zoom calls, email, but there is nothing quite like getting something in the post. Not your usual junk mail; circulars, official-looking brown envelopes, or packages you’ve been expecting from Amazon, but an unexpected letter. A surprise. Something personal that someone has spent time on. From somebody who thought about you. That’s where Mail Art comes in.

But what is Mail Art?

Basically, mail art is anything you could legitimately send though the post and anything the postal service would deliver; it could be poster art, collages, or t-shirts, It could be the contents of an envelope, the envelope itself, completely decorated, or naked mail - objects without packaging treated as mail (sticking postage stamps along a length of garden hose for example, or gluing an address label to the sole of a shoe).

Mail Art by Margaret-Rizzio Credit: Printed Matter

You can send postcards, trading cards, and even found objects (otherwise known as ‘trashpo’ or trash poetry). Pamphlets, booklets and audio cassette tapes were all popular media. Home-made rubber art stamps and artistamps (faux postage stamps) were popular, too. Formular mail was yet another approach, using form templates, often satirising government bureaucracy.

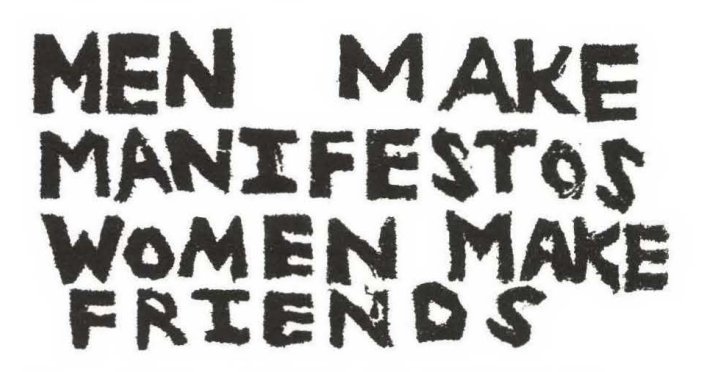

Men Make Manifestos hand-carved rubber stamp by Freya Zabitsky, 1987

Mail art can be sentimental, humorous, political or satirical, with no judgments made about the artwork or its quality. You can make Mail Art specifically for one recipient, or many, with ‘add and send on’ or ‘add and return’ instructions included with the works.

Art Mailer Chuck Welch, aka ‘Crackerjack Kid,’ talking about Mail Art, said, “It’s about the artist reciprocating in a free exchange. It’s outside of the establishment, the gallery system. It’s a reciprocal exchange, often a collaboration […] The intention is not to have a commodity that has a certain value. The value is in the exchange, the relationship, and it’s outside of money.”

“I’m amazed at what the postal service will let you send. […] You have to think about it. You don’t want to hurt the postman, so it has to be safe. You don’t want sharp edges,”–Stu Copans aka ‘Shmuel,’ Mail Artist.

So use your common sense. In 1979, the bomb squad questioned Paul Carter, aka Paul Beatless, a UK art mailer, about his 'Suspect Mailing' assemblage photographs, which were of batteries, wire, electrical and cotton wool constructions.

Mail Art’s roots can be traced backs to Marcel Duchamp, Dadaism and the Italian Futurists. In an anti-war protest, Dadaist George Grosz posted unneeded and impractical items to German soldiers at the Front during the First World War. Mail artist Ed Plunkett, however, cheekily claimed you could trace it back even further back to Cleopatra, wrapped in a carpet, having herself delivered to Caesar.

Cleopatra and Julius Caesar, © Look and Learn Magazine

In 1957, Yves Klein created a series of perforated postage stamps, painted with his International Kline Blue pigment and used them on invitations to his exhibitions in Paris at the time. It caused a bureaucratic scandal when the French Post Office mistakenly franked them as official postage stamps.

Untitled - IKB Pigment on Postal Stamp by Yves Klein, circa 1957 Credit: artnet com

However, it is the abstract artist Ray Johnson who is credited with creating the modern Mail Art movement back in 1943, but the term mail art wasn’t coined until the 1960s. Coming out of the Fluxus and Happening movements, Johnson created a community, the Correspondance School of Art, [sic] forming a network of artists across the world, with mail art going backwards and forward between correspondents. He was posting out poems, small abstract prints and collages. It relied on direct interaction between its correspondents, with some adding to works before re-posting them.

My Work/Potato Mashers by Ray Johnson, credit: The collection, The Museum of Modern Art Library

It was a way of bypassing galleries and the art establishment and connecting directly with other artists. 2021 saw a retrospective of his work, re-evaluating Johnson as a queer artist.

Other mail art networks soon sprang up. Michael Morris and Vincent Trasov created The Image Bank in Canada started circulating mailing lists and exchanging mail art.

In France, the Nouveau Realists explored mass production, consumption and disposable art, combining mail art’s rubber stamps into their works.

In 1970, the Fluxus artist On Kawara sent telegrams to his friends and family informing them that, yes, he was still alive.

On Kawara Telegram to Sol LeWitt, February 5, 1970 LeWitt Collection, Chester, Connecticut

© On Kawara. Photo: Kris McKay © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

From 1993 to 1998, Matthew Higgs adopted Johnson’s mail art concept in a project called Imprint 93, posting the works of unknown British artists to museums and galleries. As part of the project, Martin Creed crumpled a piece of paper (Work 88, 1995, on display in the Out of the Crate exhibition in Gallery 12) which Higgs sent to then-Tate director Nicholas Serota. The work was rejected and Serota’s assistant uncrumpled and flattened the work before posting it back.

Work 88 by Martin Creed ©Manchester Art Gallery

While the Chinese dissident artist, Ai Weiwei, under house arrest in Beijing in 2012, was the subject of a couple of mail art projects; Where is Ai Weiwei and Postcards to Ai Weiwei in 2012.

Then, in 2014, Ai Weiwei’s @large: Ai Weiwei at Alcatraz, an exhibition of 176 portraits of prisoners of conscience made from Lego, had a section called Yours Truly, which encouraged visitors to write messages of support to political prisoners around the world on prepaid postcards They sent over 92,000 postcards.

More recently, The Great Big Art Exhibition rejected Ai Weiwei’s own postcard mail art submission on a similar theme.

Since 2005, Frank Warren has run an ongoing community mail art project called PostSecret, where he invited the public to send in their untold secrets on anonymous home-made postcards. It still continues today.

PostSecret Screenshot

Back in the late 80s and early 90s, I was creating my own mail art. It became not just a communication with whomever I was sending it to, but a relationship with the Post Office, too. How far could I push it? What could I get away with? Alas, this was the 80s and with no mobile phones, documentary photographic evidence is lacking (back then, cameras were mainly for high days and holidays). Still, it speaks to the transitory and disposable nature of the art form.

I sent envelopes addressed with just a name and an Ordnance Survey grid reference, which arrived at the addressee’s house with a message on the envelope from the Post Office reading, ‘we know everyone by name’, which was the Royal Mail slogan at the time.

A local copy shop was offering to turn photos into Jigsaws. I did it with a letter, turning it into a 50 piece jigsaw. I also created an envelope covered with faux fur fabric.

And I constructed a snake from several long manila envelopes spray-painted green with a pair of googly eyes and felt tongue and articulated with jiffy envelope poppers (long before I knew of Ray Johnson’s book of selected works, The Paper Snake).

Then there was the Happiness Petition, based on the Royal Mail’s advertising slogan, ‘Post a Little Happiness’, with the help of an arm from a little rubber finger-monster poking out of an A4 envelope, and an appeal on the envelope to the Postal Office to stop this cruel trade in battery-farmed Happinesses, some of which were killed or injured by sorting machines and franking stamps. The back of the envelope included a petition against the cruel trade. (By the time it got to the address on the envelope, 30 workers at the local sorting office had signed the petition; a piece of formular mail art that succeeded beyond my expectations.

So, why not hone those COVID arts and crafts skills to make something and pop it in the post to someone? Or, if you have no one specific in mind, you can always try the International Union of Mail Artists.

In the meantime, I’ll leave you with this Mail Art earworm. Recorded in 1981 by Rod Summers, it name checks prominent mail artists of the time, like Anna Banana, Paul Carter, Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Vittore Baroni, Piotr Rypson, Henry Gajewski, Lon Spiegelman and Opal. The song featured in the Tate’s Live to Air Sound Works exhibition in 1982. That’s where I first heard it and it’s been in my head ever since.

And now it’ll be in your head, too.

No, no need to thank me.