Chosen by members of the Visitor Services team, Victor Newsome’s A Corner of a Bathroom (1973) is one of several recent additions making a bit of a splash in Gallery 3. So, what is there to say about a painting of a corner of a room in a corner of a room? Well, more than you’d think.

Born in Leeds, Victor Newsome (1935–2018) studied painting at Leeds College of Art from 1960 to 62 and became a Rome Scholar in painting at the British School in Rome. When he returned to England, he took up sculpture and began a career in teaching, returning to painting again in the 1970s. His works are held by the Tate, Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Library among others.

Other paintings in Victor Newsome’s Bathroom series: L) Corner of the Bathroom (1975) by Victor Newsome © the artist’s estate / photo: The Whitworth, University of Manchester C) Medicine Chest (1975) by Victor Newsome © the artist’s estate / photo: Leicestershire County Council Artworks Collection R) Corner of a Bathroom (1975) by Victor Newsome © the artist’s estate / photo: Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

Newsome’s works focus on large-scale figurative series, concentrating on heads and torsos, figures in the bath, and studies of reflections. In the Bathroom series he explores the problem of creating a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional plane, which he complicates by including the shine of the glazed tiles reflecting the intersecting planes of the walls.

A Corner of a Bathroom on display in Gallery 3 shows the corner of a bathroom devoid of objects, of any sense of self or ownership. No bathmats, or shower gels, shampoos or soaps that you’d normally find in a bathroom. There’s nothing to suggest who might use the bathroom, or what kind of person they might be; neat or messy, self-obsessed or practical. It tells us nothing. It exists in the absence of anything else, hanging in a void. The only things to see are the reflections of it in the black and white tiled surfaces, where intersecting planes mirror each other. Using thinned oils, Newsome’s brushstrokes are not clear until you come to the outer portions of the painting, where the image seems to disintegrate into its basic elements; obvious brushstrokes, pencil lines marking out the perspective and, ultimately, bare board. These underlying details of construction only resolve into detailed tiles where the axes intersect, like a focal point.

A Corner of a Bathroom by Victor Newsome (1973) © the artist’s estate / photo: Manchester Art Gallery

Newsome’s work deals with reflection in both senses of the word. The theme of reflections occurs in several other paintings in Gallery 3. Ben Nicholson’s painting, Au Chat Botte, across the room deals with the reflections in a shop window. As Nicholson explained, the shop name printed in red lettering on a glass window, is one plane, the reflections in the shop window of what was behind him, such as Barbara Hepworth’s head, is a second plane, while through the window the objects inside the shop create a third plane. He felt that, within the picture, these three planes were interchangeable so that you could not tell which was real and which was reflected.

1932 Au Chat Botte (1932) by Ben Nicholson © Angela Verren Taunt. All rights reserved, DACS 2022. Photo: Manchester Art Gallery

Nicholson’s painting deals with reflection in a narrative manner. You engage with what the reflections are of. You can wonder about the shop, what it sells, who is looking in the window and why. Newsome’s bathroom is empty of narrative. You’re just looking at pure reflection, or rather reflections of the reflections. It’s just you and the painting.

Adolphe Valette’s India House (1912), next to it, is also concerned with reflections. Depicting the electric lights of India House reflected in the River Medlock, the two works interact with each other, the arch of the bridge in the Valette echoing the apex of the corner in Newsome’s work. You can almost imagine waste water from Newsome’s bathroom being flushed out into the river in Valette’s painting.

Corner of a bathroom next to India House

Back when Valette painted the Medlock in 1912, there were dye works, cotton mills, print works, breweries, vitriol works (sulphuric acid, often used for making fertilisers but also for making chemicals use in textile bleaching processes), wood and corn mills along its banks, all pouring their waste into it every week, leaving the Medlock little more than a noxious-smelling open sewer. Not unlike today, when water companies discharge sewage and waste into rivers.

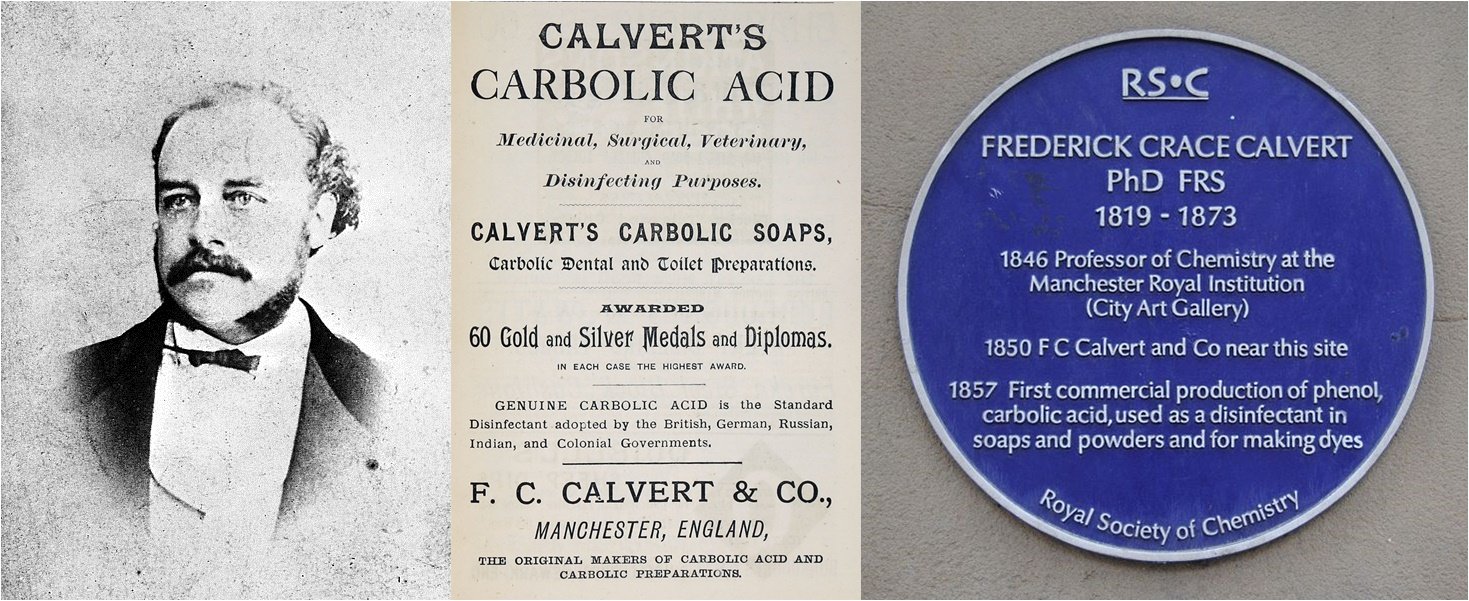

Which brings us to Frederick Crace Calvert. He was an Honorary Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Manchester Institution (now Manchester Art Gallery). Calvert rented a laboratory in the basement here and, as part of his rent, gave lectures on chemistry to the great and the good. He’s best known for developing the commercial production of phenol or carbolic acid, which was used as an antiseptic in everything from carbolic soap to–ta-daaa- treating raw sewage. In order to produce it, in 1865 he established a large works in Manchester, making and selling his own cleaning and bathroom products.

L) Portrait of Frederick Crace Calvert © Wellcome Library C) 1893 advert for F.C. Calvert & Co. source: Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History R) Royal Society of Chemistry plaque commemorating Fredrick Crace Calvert, Princess Street, Manchester.

And while we’re back in the past, Gallery 3, where A Corner of A Bathroom currently hangs, turns out to have been an actual bathroom. The Gents, to be exact. Back in 1889, they were up on the first floor, with the Ladies over in Gallery 11. We’ve moved them since then, so don’t get any ideas. We deal firmly with any toilet troubles.

Manchester Art Gallery 1889 Exhibition catalogue plan

The black and white institutional tiles in Newsome’s painting are reminiscent of public toilets, too, relating to the fact that the Gallery, a public building, also has public conveniences. In fact, one of the most asked questions we hear from visitors is ‘Where are the toilets?’

Public conveniences themselves first became available in 1851, during the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace. After that, these ‘Public Waiting Rooms’ began popping up everywhere, but mostly for men. Without Public Waiting Rooms of their own, women still found themselves tethered to their homes by the ‘urinary leash’, which restricted how far they could travel from the home, although things did eventually change.

Public toilets have seen a decline in recent years, though. Now the only public toilets in the city are situated a stone’s throw from each other, in the Central Library, the Town Hall and here in the Gallery. Therefore we’re always happy to direct desperate people in the bathrooms’ direction. The real ones, that is, not the painting, although we can do that as well.

Manchester Art Gallery Toilet signage

For many people, bathrooms can be a space for reflection; a quiet, contemplative, creative space. They are a place where we feel the safest, a place where we’re stripped bare, physically and emotionally. Everything we do in the bathroom is a ritual done thousands of times, demanding no thought. You’re away from other distractions. Standing in the shower, lying in the bath, or sitting on the loo can be quite meditative. It’s the perfect time and place for sparks of inspiration to ignite ideas. With no interruption, you can allow those deep and philosophical shower thoughts to bubble to the surface.

The Fisher King (1991) directed by Terry Gilliam credit: TriStar Pictures

Some people get their best ideas in the bathroom, starting with Archimedes and his ‘Eureka!’ moment. Agatha Christie is another one. She used to write in the bath while eating apples. Oscar-winning screenwriter Dalton Trumbo (he wrote the screenplay for Spartacus, amongst other things) also wrote in the bath, accompanied by his pet parrot. Pharrell Williams, too, claims to find inspiration there, along with Ed Sheeran and Shigeru Miyamoto, the famed Nintendo video game designer, who said he found inspiration for the video game Donkey Kong while luxuriating in the company bathtub.

Looking at A Corner of a Bathroom, it’s very black and white. On or off. Binary; like a computer or a brain. Could it be a representation of the human mind? Maybe we shouldn’t be focusing on the centre of the painting and working out, but starting at the edges and working inwards. You can see the ‘idea’ of a bathroom coming into existence at the edges, resolving and crystallising, coming into focus at the centre, where the axes meet, as the fully realised corner of a bathroom. If the central part of the painting in sharp focus is the conscious part of the mind, are the shadowy edges the darker recesses of the mind, the subconscious; the darkness around the campfire?

Another work that depicts the creation of thought is Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. It’s been suggested in recent years that God is portrayed in the form of the human brain. Michelangelo believed that divine guidance came though the intellect, his composition suggesting that thought is divinely inspired.

The Creation of Adam (circa 1511) by Michelangelo Photo: Wikipedia

Does A Corner of a Bathroom do something similar? Does it depict the creation of thoughts surfacing from the subconscious, reflecting what is happening in our minds as we look at the painting and consider what it means?

While The Creation of Adam affirms man’s existence in creation, A Corner of a Bathroom seems to question it hanging, as it does, in space. It’s the very basis of phenomenology. We know we exist as an individual, but we’re hanging there in a void, like A Corner of a Bathroom. How do we know the rest of the world exists? What evidence do we have other than that of our own senses?

Darkstar (1974) directed by John Carpenter

Perhaps, on reflection, you might choose to use those senses to ground yourself in reality, rather than question it, and focus on the painting in an act of mindfulness.

So finally, having plumbed the depths of A Corner of a Bathroom, does the painting leave you

or

This post was developed from a discussion with Helen from Visitor Services about the painting for its accompanying information text panel.