Inspired by our film review of The Duke, about Kempton Bunton’s theft of Goya’s painting of The Duke of Wellington from the National Portrait Gallery back in 1961, we continue our look at Manchester Art Gallery’s own brushes with the law.

With CCTV cameras installed at the gallery in 1966, you would have thought that would be an end to the wrongdoing at MAG, but no. Far from it. In 1967, Manchester Art Gallery had several branch galleries around the city; The Old Parsonage at Fletcher Moss in Didsbury, Heaton Hall, Platt Hall, Wythenshawe Hall and Queens Park. They proved to be easier targets than the city centre gallery.

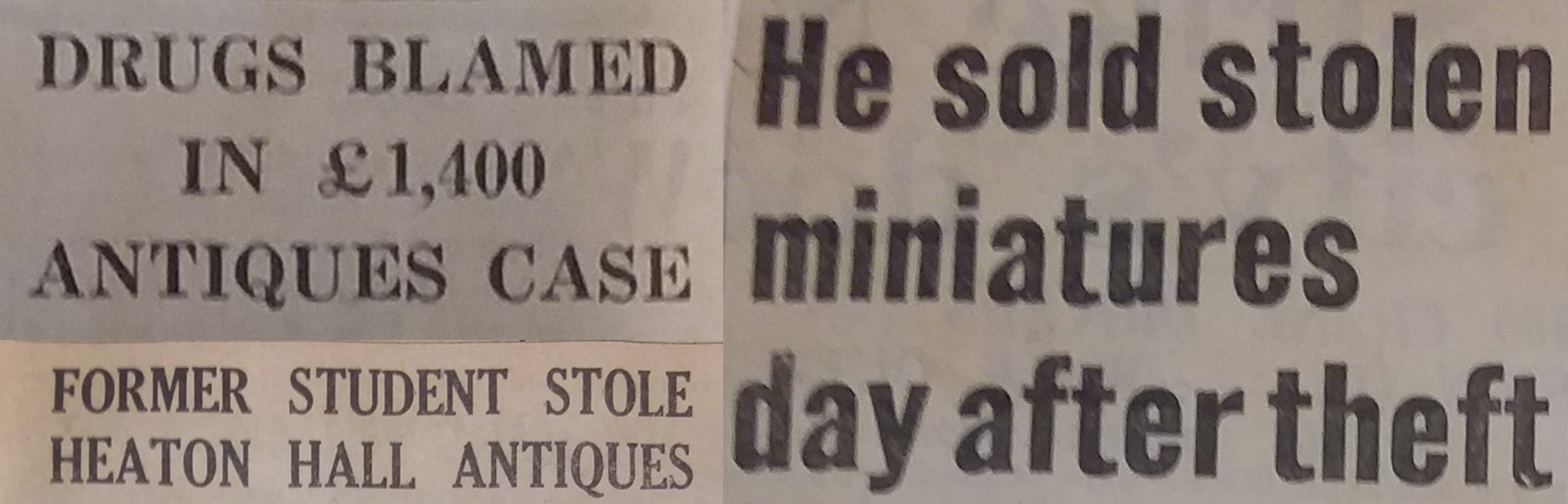

(Top left) Daily Telegraph 26, 10, 67 (Bottom left) Prestwich & Whitefield Guide 27.10.67 (Right) Manchester Evening News 23.10.67.

On the evening of 9th March, 1967, 22 antique enamelled miniatures from the Harold Raby Collection, worth £1,400, were stolen from Heaton Hall, Heaton Park. A man calling himself Mr Lemay approached five reputable Manchester antique dealers the next day to sell them. Two of them later identified the man as 24-year-old Michael Davies, a former Liverpool University student and now a self-employed antiques dealer. He already had a criminal record of antique theft and had served four prison sentences. He was also on probation for stealing £1,700 worth of antiques from Tatton Hall in Knutsford that May. Things weren’t looking good.

The Defence, Mr O.N. Wilkinson, said that they were dealing with, ”a boy of excellent background and considerable scholastic standards, who has gone completely off the rails. I think it is true to say that drugs started him on this downward career.” The jury acquitted him of the theft, but found Davies guilty of receiving and attempting to sell stolen goods. The judge gave him a three year conditional discharge.

Doctor Harry Piggot, the Chair of Manchester Art Galleries Committee, admitted they’d had “a number of small thefts in recent years and have been advised by the chief constable to tighten our security precautions as an insurance against a possible bigger theft. After all, we have one collection alone, which is insured for more than £1M.”

They’d tried police whistles. They’d tried CCTV. This time they’d leave nothing to chance. Enter Detective Chief Inspector Herbert Scattergood. On his retirement, the second in command of Salford C.I.D. became the first police officer in charge of security at the Manchester City Galleries.

(left) Manchester Evening News 28.11.67 (right ) Salford City Reporter 01.12.67

It all went well for a few years and no doubt the director and the councillors of the Art Galleries Committee heaved an enormous sigh of relief. Too soon, it seems.

At 3.45pm on Thursday November 11th, 1970, a dark green 3-ton van carrying 34 Italian Renaissance small bronze statues and 40 paintings left the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, bound for Manchester Art Gallery, where they were due to go on display until January 2nd. The collection was part of a touring exhibition on loan from the V&A. The trip should have taken 90 minutes, but after leaving Liverpool, the van disappeared.

(Top left) Daily Telegraph 12.11.70 (Bottom left) Daily Express 12.11.70. (Right) Daily Sketch 12.11.70.

Manchester Art Gallery raised the alarm when the van did not arrive as expected that afternoon. With so many recent art thefts in the country, they thought that a criminal gang could have hijacked the van. Every police officer on duty in Manchester was looking for it. The police of Lancashire, Staffordshire, Gwynedd, Manchester and London were mobilised and a massive dragnet began for the missing van. They set up road blocks from Liverpool and searched large vehicles, along with car parks and lay-bys on the route. The two London drivers from the V&A, Harry Hudson and Bert Waller, were also missing.

It was 3.45am the next day when police found the van ‘hijacked and dumped’ on waste ground in Manchester and they took the van to the police pound in Longsight. In a twist, the driver contacted the police that morning to report that his van had disappeared. The police quizzed Bert Waller for three hours until the story emerged.

The journey from Liverpool to Manchester took Harry and Bert longer than expected because of rain and heavy traffic. They arrived in Manchester after the Gallery had shut. Bert Waller takes up the story. “We left Liverpool at 3.45pm but didn’t reach Manchester until 7.30. The Gallery was closed, so we found lodgings for the night. It is normal procedure for us to park the van overnight if an art gallery or museum is closed. We took it up to Hyde Road and parked it on a piece of waste ground and I could see the van from my bedroom window.”

The police said it had all been a misunderstanding.

(far left) Daily Telegraph 13.11.70 (left) Western Evening Herald 12.11.70 (right) Lincolnshire Echo 12.11.70 (far right) Manchester Evening News 12.11.70

Bert stated; “I’m fed up with people interfering. I knew the van was safe. I locked the van with special government keys and set the alarm. Even the police couldn’t reach the load. […] I’ve told my employers I’m packing the job in. If the museum had not interfered and told the police, everything would have been okay. This is the second time I’ve been involved in one of these incidents.” (Bert Waller had ‘lost’ a shipment in Aberdeen. Police found a consignment of silver worth several thousand pounds after the Victoria and Albert Museum had informed them it was missing). “I’m sick of people doing our job for us,” he went on. “We like to keep our movements quiet and that’s why we made no phone calls.”

“He should have rung Manchester the minute he knew he was going to be late. And he certainly should have rung us,” said a spokesperson for the V&A.

Harry Hudson (left) and Bert Waller (right) Photo: Manchester Evening News ©M.E.N.

Then, after a lull, in July 1976, there was a spree of bold art thefts across Manchester. The first theft occurred when Manchester Art Gallery found a small oil painting, Cupid and Venus by Henri Fantin-Latour, valued at £750, to be missing. The theft had happened in broad daylight, while the gallery had been open to the public. Next, on the night of July 16, a window was smashed at the Fletcher Moss Branch Gallery in Didsbury, and the thief made off with three pictures; a watercolour of East Bergholt Church by John Constable and two by Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, including a watercolour of Venice.

(left) Cupid and Venus by Henri Fantin-Latour (centre) East Bergholt Church (c1806) by John Constable (right) Landscape after Turner’s ‘The Dogana, San Giorgio, Citella, From the Steps of the Europa, Venice, by Hercules Brabazon Brabazon © Manchester Art Gallery

Two days later, on July 18th the Whitworth was hit. Smashing a ground-floor window, the thief got away with three drawings by Thomas Gainsborough, a Gaspard Poussin, and a Cornelis Van Poelenburgh, all unofficially valued at a total of £50,000.

Detectives soon eliminated a theory that it was the work of a specialist art thief or amateur collector, especially when a man with a local accent phoned a newspaper to claim responsibility for the thefts.

(Top left) Daily Telegraph 19.07.76. (top right) Manchester Evening News 17.07.76 (bottom) Manchester Evening News 20.07.76

The police later arrested Philip Thorne, a painter and decorator from Longsight. Appearing in court, he was charged with burglary and thefts from Fletcher Moss and The Whitworth (but not for the theft of the Fantin-Latour) and remanded in custody. On a second hearing, he was released on bail – and promptly absconded. In September, a warrant was issued for his arrest and, a year later, he was caught and sentenced to two years imprisonment for theft.

As for Manchester Art Gallery, it undertook a £70,000 programme to safeguard collections estimated to be worth more than £12 million at the time. The improved security programme included at least £18,000 of “additional electronic protection and installation of systems for detection of fire, flood and other risks.”

But would it be enough to stop further mischief and malfeasance at MAG?

Find out in Part Four.