Inspired by our film review of The Duke, about Kempton Bunton’s theft of Goya’s painting of The Duke of Wellington from the National Portrait Gallery back in 1961, we continue our look at Manchester Art Gallery’s own brushes with the law.

In the early 1960s, after the theft of the Goya, there were several other high-profile art thefts, including a £400,000 haul from the O’Hana Gallery in Mayfair.

The Sunday Times 15th July 1962

The press soon cashed in, chasing headlines of stolen art treasure. At the Evening Chronicle two reporters and a photographer devised a stunt to ‘test’ security at Manchester Art Gallery by ‘stealing’ a painting. On the 12th June 1962, they entered Gallery. They smuggled in a false collapsible frame, then smugly smuggled it out again, pretending to have stolen a painting.

Evening Chronicle 12th June 1962

Galleries across the country were generally unprepared for the spate of art crimes. In The Sunday Times, 15th July 1962, one London gallery director said of security that, until recently, “a mortise lock seemed all that was required in some cases.” While a spokesperson for a leading fine art insurance company admitted that his firm “rarely insisted that burglar alarms be fitted because incidents of loss were so low”.

The Guardian 13th July 1962 © Guardian News and Media Limited

By now galleries across the country were now on high alert. Fearing raids by international art thieves, they took steps to avoid a similar fate. Mr S. D. Cleveland, then Director of Manchester Art Galleries, had discussions with the police. As a result, the Gallery introduced several additional safety measures, and the staff were told to be on constant vigilance.

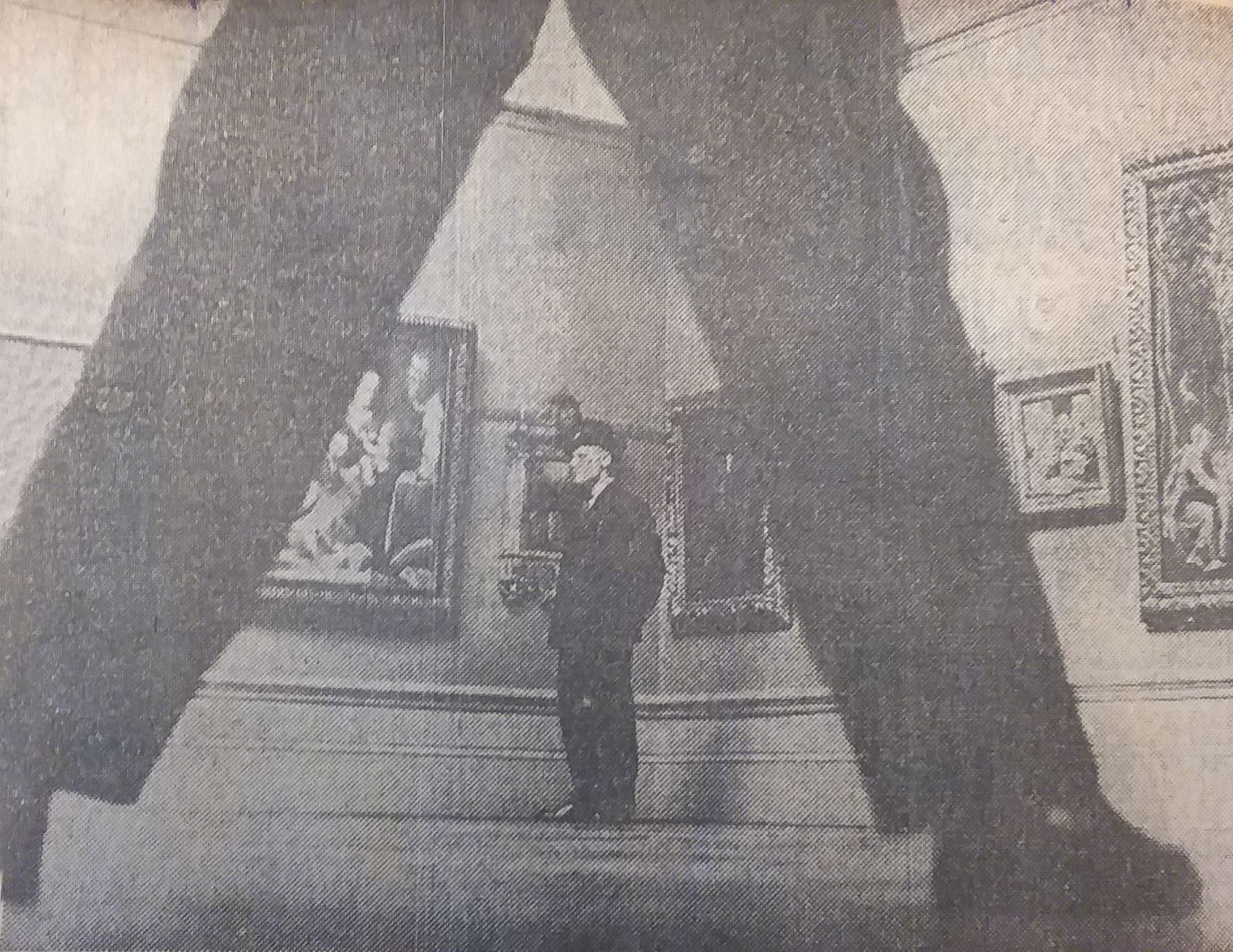

Gallery Attendants on duty at Manchester Art Gallery © Manchester Evening News

So how long did that constant vigilance last? About four months. On the 9th of November 1962, William Durnan, a homeless man from London, walked into the gallery and walked out again with Jean-Francois Millet’s Peasant Girl under his arm.

Peasant Girl (1870-1880) by Jean-Francois Millet © Manchester Art Gallery

Durnan later walked into the Manchester offices of the Daily Express with the painting under his coat and handed it over, saying, “I just wanted to prove the security at the gallery was bad.” The newspaper handed the painting back to Mr James Gatt, assistant curator at the gallery, who said: “I don’t know how it was taken without our noticing it. We had closed for the night. We had no idea one of our paintings was missing.”

Newspaper headline: County Express 22nd November 1962

William Durnan appeared in court on the 19th November charged with stealing the painting worth £350 and causing 1 shilling of damage to the gallery wall. Mr Gandy, prosecuting, explained that on November 9th Durnan (55) travelled from Preston to Manchester on his way to London but, having no money, ended up at the Gallery. A Londoner, Durnan, hoped to get money for his fare home from the newspaper by selling his story. According to his statement, he remembered reading in a newspaper how simple it was to “get anything out of a gallery”. Durnan went to the first floor of the Gallery about 4pm and, when unobserved, ripped the 18 inch by 12 inch painting from the wall and put it under his coat. At 5:30pm that evening, he turned up at the newspaper offices and tried to get money from them by telling them what he had done. The newspaper immediately returned the painting to the Gallery, and the police detained Durnan at Great Ancoats Street. The court fined Durnan 5 pounds, 5 shillings with sixteen shillings in costs.

But it wasn’t all about crime being perpetrated against the art gallery in the 60s. There was the time that Manchester Art Gallery profited from the illicit sale of pornography. No, really. But it’s not what you think, honest, guv!

In 1964, an advert appeared in the personal columns of several newspapers and men sent off their money to a post box number in Manchester, expecting to receive lewd books and photographs in return. They never received them. Instead, a police investigation of the scam seized £5,500.

Top left: Glasgow Daily Record headline, 29th August 1964. Top right: Daily Mirror Headline 29th August 1964. Bottom left: Daily Mail headline 29th August 1964. Bottom right: Manchester Evening News 29th August 1964.

Despite a plea from the police for the conned men to come forward, the men who had responded to the advert were too embarrassed or scared to claim their money back. Magistrate F. Bancroft Turner turned the ill-gotten gains over to the Lord Mayor’s Common Good Trust Fund to be distributed among charitable causes. He also told the trustees that £1000 was to be given to Manchester Art Gallery, saying, “It is one way of providing a decent form of art instead of the indecent kind. It might be considered a form of rough justice.”

Then, in 1966, wanting to increase security at the galleries after deciding that ‘constant vigilance’ just wasn’t cutting it, it was recommended that the Council trial a closed-circuit television camera system at one gallery as an experiment, to further safeguard the art treasures of Manchester which at the time were insured for around £500,000.

Newspaper clippings Top: Daily Telegraph 4th January 1966. Bottom: The Sun 4th January 1966

The Council agreed and they installed new CCTV cameras at the City Art Gallery on Mosley Street at a cost of £550.

CCTV station in the Gallery entrance hall ©Manchester Art Gallery

How far would this new-fangled technology go in improving the security at the gallery, and stopping art thefts? And would it be better or worse than police whistles?