People have always sought ways to mark the passage of time. For a long period, the only way to tell the time was by astronomy, using the sun, moon and stars. Using stone circles, sundials, astrolabes, water clocks, candle clocks, and hourglasses, people gradually refined their ability to tell the time.

In the late 1300s, driven by a need to regulate religious life, monks developed the first mechanical clocks. They would strike a bell to mark various daily ritual observances (the Latin word clocca, meant bell). These, however, had no dial, were unreliable and needed constant setting using sundials.

It was only in the 1600s that mechanical timekeeping advanced with the invention of the pendulum clock by Christiaan Huygens. The pendulum helped regulate the clock mechanism so that time could be kept more accurately. Between that and the development of the mainspring, timekeeping became not only more accurate but could be reproduced at a smaller scale. So from large public clocks, it was possible to make pendulum powered long-case clocks for use in the home (if you were rich enough).

(l) Longcase clock by John Bagnall (c) Longcase clock by Peter Garon (c.1700) (r) Longcase clock by William Lawson (1716-1822) ©Manchester Art Gallery

The 1700s saw more advances in horology, the study of time measurement. It became possible to tell time with increasing accuracy and led to the development of watch clocks small enough to carry in a pocket.

In the 1700s, Manchester was a small market town. It was, however, a hotbed of horology. It had a thriving clock-making industry, long before it became the industrial cotton powerhouse we know today.

Detail of John Berry’s Plan of the town of Manchester and Salford in the County Palatine of Lancaster (1751)

Manchester Art Gallery, as well as having several longcase clocks in its collection, has added other time pieces over the years, only one of which is on display; a magnificent pocket watch made by Thomas Ollivant, which you can find in gallery 3.

watch (l) front and (r) reverse, by Thomas Ollivant created c.1835 © Manchester Art Gallery

Thomas Ollivant Born in 1787. For a time, he lived at 26 Mosley Street. He was a member of a silversmithing and clock-making family consisting of mostly Johns and Thomases just to confuse things. His father, John Ollivant, had premises in Exchange Street. In time, Thomas and his brother, John Josiah, joined the family business, and it became Ollivant & Sons. Then, with the addition of another family member, it became Ollivant Sons & Nephew. The business later moved to St. Ann’s Street.

“The large and elegantly appointed showrooms (all the fittings of which are completed in the most costly and elaborate style), have six fine windows facing St. Ann’s Street and Police Street, and form one of the most commodious and attractive establishments of the kind in the city.”

- Grimswades pg721

Manchester Faces and Places, May 1890, says that, “Mr. Ollivant was greatly respected in Manchester for his liberality and philanthropy.”

While better known for his clocks and watches, Thomas Ollivant was also a silversmith. He registered his silver mark ‘T O’ at 16 Exchange Street on 12 May 1796, having already registered his mark in London.

Thomas Ollivant’s registered silver mark Credit: silvermakersmarks.co.uk

We also have a couple of pieces of his silver in our collection, too. But he often bought in stock from other silversmiths and over-stamped them with his own mark, such as the silverware from Peter and Ann Bateman. This form of branding was to ensure the quality of the work for his customers.

Silver spoon front and back by Thomas Ollivant (1798), silver marrow scoop by Thomas Ollivant (1800) © Manchester Art Gallery

Around 1855, in his later years, Thomas Ollivant went into business with a neighbouring clock-maker, Mr. John William Botsford. Thomas Ollivant died in 1868 and John Botsford in 1881. The business was then run by Mr Botsford’s brother, but retaining the name.

The business of Ollivant and Botsford outlived the pair and continued in Manchester until 1958, when Mapin and Webb took over the business.

Ollivant & Botsford adverts (l) 1894 (r ) 1898 credit: Hallmarks Database and Silver Research

The gallery also has a couple of other time pieces by Thomas Ollivant.

(l) Watch movement by Thomas Ollivant (c) Reverse of watch movement by Thomas Ollivant (r) Stopwatch by Thomas Ollivant ©Manchester Art Gallery

But the longcase clocks and small pocket watches still needed to be set to the correct time. The public could do this by means of public clocks, or a more accurate clock called a “Jeweller’s regulator”, set in a watchmaker’s window so that passers-by could correct their pocket watches. Public clocks were also another way to do this. These would be set by clock-makers, too. One such man was Peter Clare (1781-1851), who eventually had the responsibility of regulating Manchester’s public clocks, like the old College Church clock.

The Old College Church and Clock (later the Cathedral) with Victoria Bridge from Bradshaw’s Manchester Journal, May 1841.

All this was well and good for local people, but local time caused problems for the growing nationwide railway network. Because local times were still set by the sun, this meant that each town had their own local mean time. Each locality set its own time by sundial.

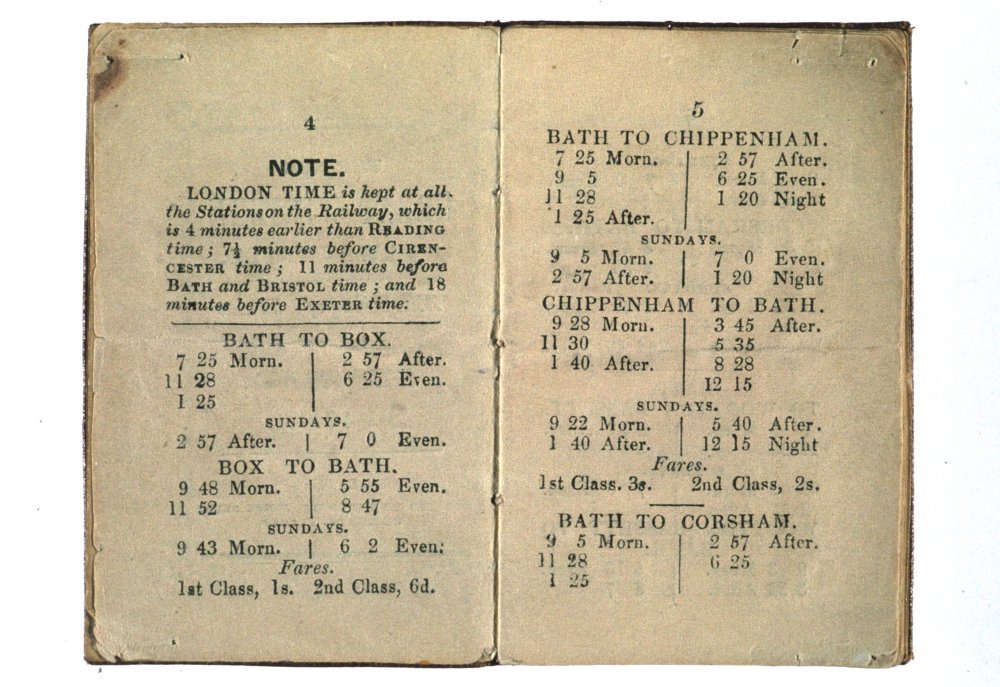

The New Western Railway timetable, Alteration of trains for the summer 1844 credit: sciencemuseum.org

As a result, some public railway clocks often had two minute hands, one for local time and one for London time. London was always ahead of any town west of it. How far ahead depended on how much further west you were. Places one degree of longitude apart had times of four minutes difference. Not only could this cause problems with timetables and connections, but it could lead to accidents and collisions.

So, in 1840, Great Western Railway began introducing a standardised ‘railway time’, synchronising all its local mean times with that of Greenwich, London. By 1846, the Great Northern line introduced standard time to the Leeds, Liverpool and Manchester stations; Manchester otherwise being about 8 minutes behind London. By 1855, almost the entire country now ran on one uniform time, adjusted to Greenwich time by electric telegraph. Britain legally adopted Greenwich Mean Time in 1880.

But it wasn’t just the trains that were regulated by clocks. Mill owners got in on the act, too, with the clock regulating mill workers' lives. The new industrial machines of the cotton industry bode well for the clock-makers of Manchester. They were ideally placed to make, assemble and maintain the new machinery.

The mill owners also wanted to be sure they were getting every minute of work from their workers and that they kept the rate of production up. To this end, Mill Clocks were invented. These clocks had two dials. The clock mechanism itself would run one; ‘real time’. Shafts connected the other dial to the water wheel or steam engine that powered the mill, and that showed “mill time”. If the waterwheel (and thus the clock) ran slowly, then the workers would still have to work their allotted hours as determined by ‘mill time’ rather than real time.

Double dialled longcase mill clock by from Park Green Mill, Macclesfield (1810) ©Board of Trustees of the Science Museum Citation

Another innovation was the peg clock, noctuary, or tell-tale clocks, often used in mills for night watchmen, to make sure they didn’t stint on their rounds. Set up around the factory, the dial of the peg clock had pegs or pins around the outside of the clock dial which rotated. The clock was in a sealed case to prevent any tampering with the mechanism. The peg, when depressed by a lever, would mark a piece of card or paper roll, recording the time of the watchman’s presence.

Noctuary Clock or Peg Clock by John Whithurst III, © Derby Museum and Art Gallery

The Manchester clockmaker, Peter Clare, also made one of these types of clocks.

We’ll look at him in PART TWO.