Okay, we’re going back in time again. Pick your mode of transport and meet me back in 1842.

Credit: Warner Bros Credit: BBC Worldwide Credit: Universal Studios

So, the Royal Manchester Institution for Science, Literature and the Arts formally opened its doors to the public in 1835 and, in 1838, the building was fitted with gas lighting, enabling evening openings (eat your heart out First Wednesdays!).

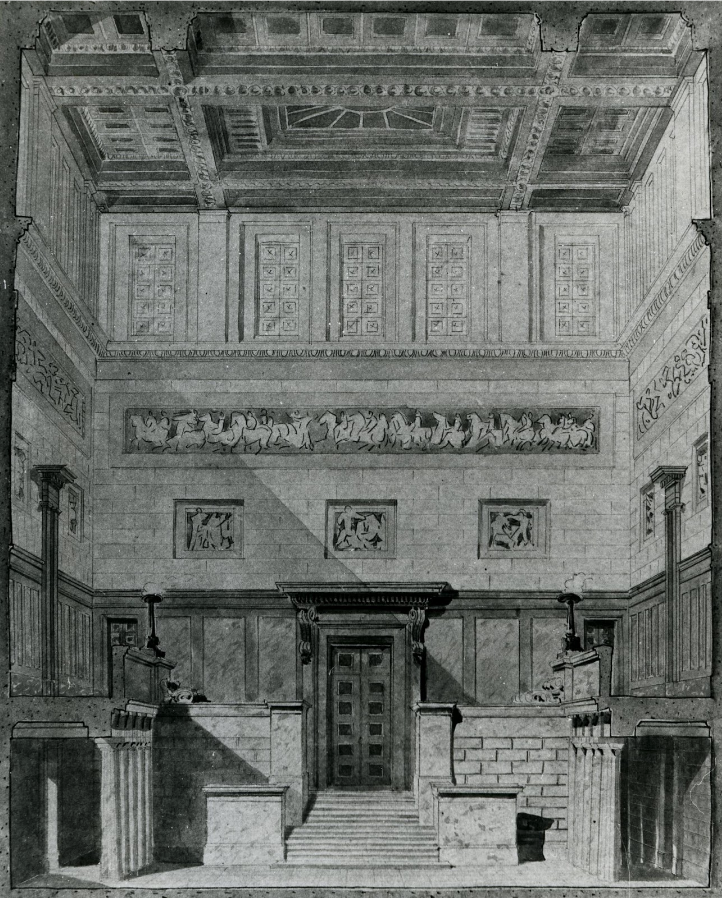

Royal Manchester Institution, line engraving by J Fothergill credit: Manchester City Galleries

So what would you see if you were to visit back then? An article from the Manchester Guardian in April of 1842 gives us an idea. Although, to be quite honest, the reporter was a bit of a size queen, constantly quoting the dimensions of each and every room, so I’ve left those out. After all, it’s not the size of your gallery that matters, it’s what you do with it that counts.

Most of us wouldn’t get in, however. The men that financed the institution did so on the understanding that it wouldn’t support any mixing of the classes. As such, the working classes were effectively banned from the RMI. By now though, they had their own institutes for the diffusion of knowledge, both thanks in part to George William Woods, who had also championed the formation of the RMI; there was the Mechanics Institute and, in 1836, a new addition just behind the Royal Manchester Institute itself, The Athenaeum (more on that in a future instalment).

Even supposing you made it through the class barrier, unlike today, it wasn’t free entry. The RMI Committee had burned through nearly all their money building the place, so they had to raise yet more for the running of the institution. How did they do that? Crowdsourcing again.

They appealed once more to the rich patrons of Manchester in what was basically a Victorian Kickstarter, offering several tiers of membership for varying levels of pledged subscriptions:

RMI membership tiers

Once you’d got over that hurdle, as you made your way to the portico entrance you’d see the six sculptural panels on the front of the building created by John Henning the younger in 1833, three either side, portraying the teaching of various subjects, in a reference to the classical libraries and temples that the Committee sought to imitate; Sculpture, Architecture and Painting on the left hand side.

John Henning’s sculptures adorning the north wing of the RMI, Sculpture, Architecture and Painting

Credit: Manchester City Galleries

And Mathematics, Wisdom (represented by the figure of the Roman Goddess Minerva) and Astronomy on the right. But originally they weren’t supposed to be there, at least not in their current form.

John Henning’s sculptures adorning the south wing of the RMI, Mathematics, Wisdom and Astronomy

Credit: Manchester City Galleries

In 1829, Charles Barry hand-picked Richard Westmacott to provide sculptures for the building at a cost of £2,000, which ruffled the feathers and tightened the purse strings of the bluff northern RMI committee. They refused to pay such an exorbitant amount. After a long drawn-out argument with Barry a compromise was reached. Henning was engaged and paid the much cheaper sum of £30 a piece for six sculptures. He even had the foresight to saturate them in a wax solution in an attempt to protect them from the worst of Manchester’s industrial elements. And boy, were they going to need it.

Once you’d passed those, then it’s up the steps and, as the Guardian reporter states, “Visitors and members of the Institute on entering by the principal entrance of the Royal Institution, Moseley Street, find themselves in the outer hall.”

Watercolour of the RMI Entrance Hall by J Hance, 1838 credit: Manchester City Galleries

With dramatic lighting like that you half expect to find Indiana Jones or Lara Croft exploring the place...

Designed as a top-lit sculpture court, the Institute’s entrance was decorated with Richard Westmacott’s casts of the Parthenon marbles, gifted by King George IV in 1830, which were one in the eye for Barry. The RMI now had some of Westmacott’s work, and what’s more, they’d got it for nowt! Interestingly, Henning’s dear old dad, John Henning Sr. also had an interest in the marbles, being allowed to sell exquisite miniature casts of them (two of which are currently on display on the Balcony). Unfortunately, cheap European knock-offs led to his financial ruin and he died a pauper.

Here, you could also apparently see a ‘splendid full-length marble figure by Francis Chantrey of Dr. Dalton … within the hall of the institution.’ This has long since been removed to the Town Hall.

Original Ground Floor Plan of the RMI by Charles Barry, showing the pit of the lecture theatre, which is now the gallery shop credit: Manchester City Galleries

But back to our reporter; “On each side of this [hall] in front, are several small rooms; those to the left, in the north wing of the building, (which today contains galleries 1 and 2) are expected to be appropriated as a porter’s room and ladies’ cloaking rooms etc,; there are several other good rooms, including the council room, the room originally intended for the library and the [Drawing School] all directly accessible by the corridor from the entrance hall.”

Detail of the North Wing Ground Floor Plan showing what is now Galleries 1 & 2 and the Mary Gregg Meeting Room credit: Manchester City Galleries

“[There are rooms] in the other wing for gentlemen’s hats, cloaks etc. Proceeding along the corridor to the right, visitors will pass through three rooms in the south wing, (now the Gallery Café) in the occupation of [the Natural History Department]; the third innermost of which adjoins the lecture theatre. Such is the general disposition of the ground floors.”

Detail of the South Wing Ground Floor Plan showing what is now the Gallery Café & Drawing Room and the Charles Rutherston Meeting Room credit: Manchester City Galleries

And then we go upstairs to the first floor; “The uppermost floor of the building, ascent being had from the entrance hall of the Royal Institution [leads to] to the Sculpture gallery, which extends over three sides of the hall and adjoining corridors. The corridor leading to the north wing opens into the suite of rooms called the picture gallery, (now known as galleries 3 – 6) which are generally occupied by the annual exhibition of paintings, the works of modern artists. Of these the first two rooms, being separated only by columns, may be taken as one room, lighted by lanterns in the roof.”

Original First Floor Plan of the RMI by Charles Barry, showing what is now galleries 3 – 11 along with the gallery of the lecture theatre which is now Gallery 7 credit: Manchester City Galleries

“The corridor to the right leads from the sculpture gallery to the Manchester Choral Society’s room, and its ante-room in the south wing of the building (now galleries 8 – 11). This ante-room is at present the depository of a number of paintings, the property of the Royal Institution.

In order to keep more money flowing into the coffers, the Institute hired out rooms to various societies for annual rates. In 1842, the galleries now known as 9 and 10 were occupied by the Manchester Choral Society for the sum of £100 a year.

Original First Floor Plan of the RMI by Charles Barry, showing what is now galleries 3 – 11 along with the gallery of the lecture theatre which is now Gallery 7 credit: Manchester City Galleries

From the entrance hall, a door from the central stairs led to… “the lecture room of the Royal Institution [which is] is semi-circular and divided into pit and gallery, of which the former contains accommodation for 448, and the latter for 224 persons, a total of 672.”

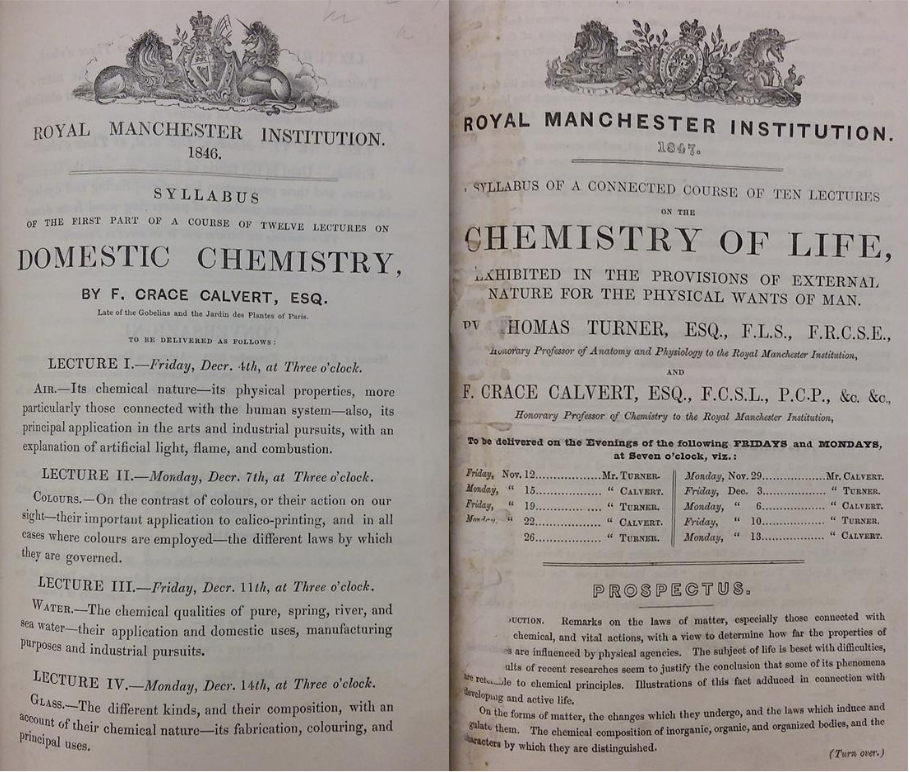

This was where, if you were a member (and if you’d got this far, you obviously were), you could take in lectures on a wide range of topics. The Royal Manchester Institution provided regular lectures series on the recent developments in science, mainly for its upper middle class and professional membership, as well as conversaciones, formal conversations on particular topics.

Selection of lecture syllabuses given at the RMI credit: Manchester City Galleries

The basement of the building even contained a teaching laboratory. One of the scientists to work there was the industrial chemist, Frederick Crace Calvert (not to be confused with Frederick Crace, who was King George IV’s interior designer – another little pub quiz nugget for you there). Crace Calvert was noted for his work on the industrial manufacture of carbolic acid, or phenol, which was used in the textile industry for dyeing. Its antiseptic properties were also used for treating raw sewage, which brought it to the attention of Joseph Lister, who developed it for antiseptic surgery. As one of the honorary professors of the Institution, Crace Calvert was also expected to lecture to the membership at least four times a season.

Examples of Frederick Crace Calvert’s RMI Lectures credit: Manchester City Galleries

If you exit by the (present day) café entrance, almost opposite, across Princess Street you can see a Royal Society of Chemistry plaque commemorating Crace Calvert.

Frederick Crace Calvert’s Royal Society of Chemistry plaque on Princess Street

Interestingly, even in 1842 there were plans afoot to join the Royal Institution to the Athenaeum building across the street, much as they are today, which was the original reason for the reporter’s visit.

“We mentioned in our publication … a plan which had been suggested for connecting the Royal Institution and the Manchester Athenaeum into one suite of buildings, with a lobby between, extending over Back George Street, on the level of the first floor and communicating with both buildings– the connexion between them made by a passage about eleven feet wide … Plans have been prepared for carrying the intention into effect. Thus two edifices, kindred in design and object, the work of the same architect (Mr Charles Barry), will be united in one comprehensive plan.”

However, the committee never finalised the plans and nothing ever came of the proposal. The Gallery would have to wait a further 158 years for that idea to come to fruition.

All of which brings us nicely… back to the future.

Credit: Universal Studios