Boris Taslitzky’s Riposte (1951) is currently on display as part of the Let’s Get Together and Get Things Done exhibition in galleries 17-18. A riposte is a quick, sharp spoken reply. It’s also a fencing term for a quick counter attack thrust. The painting depicts the French riot police violently putting down a dockers’ strike. While the title, Riposte, can ambiguously refer to either the dockers or the police (depending on the viewer’s politics), Taslitzky was very much on the dockers’ side. The violence of the clashes and the use of dogs reminded Taslitzsky of Nazi tactics during the occupation of France so much that he pointedly gave the face of Adolph Hitler to the policeman in the foreground.

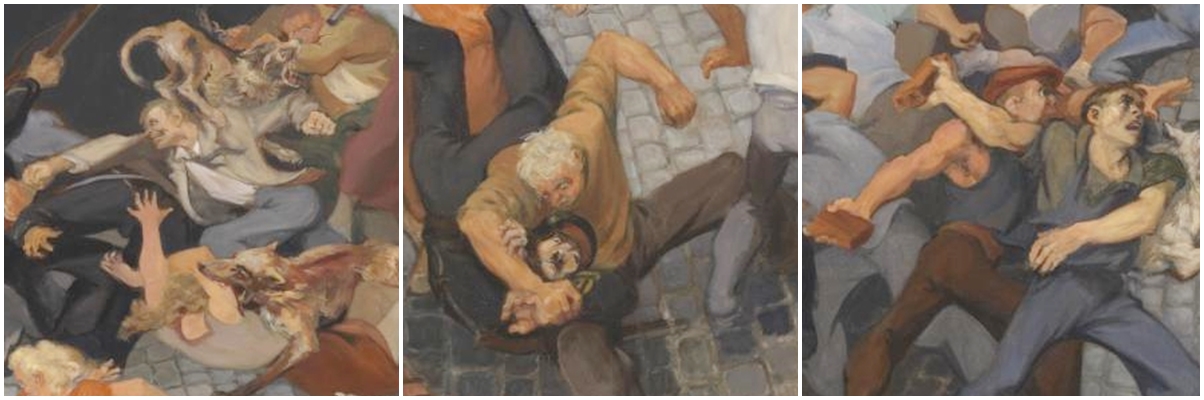

Riposte by Boris Taslitzky (1951) © Tate 2019 / © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

One of the things that struck me most about the painting was the sheer energy of the composition. This is no posed tableaux. Taslitzsky depicts the lunges, punches and lobbing at their extremes of movement, strengthening the feeling of action and immediacy.

Details - Riposte by Boris Taslitzky (1951)

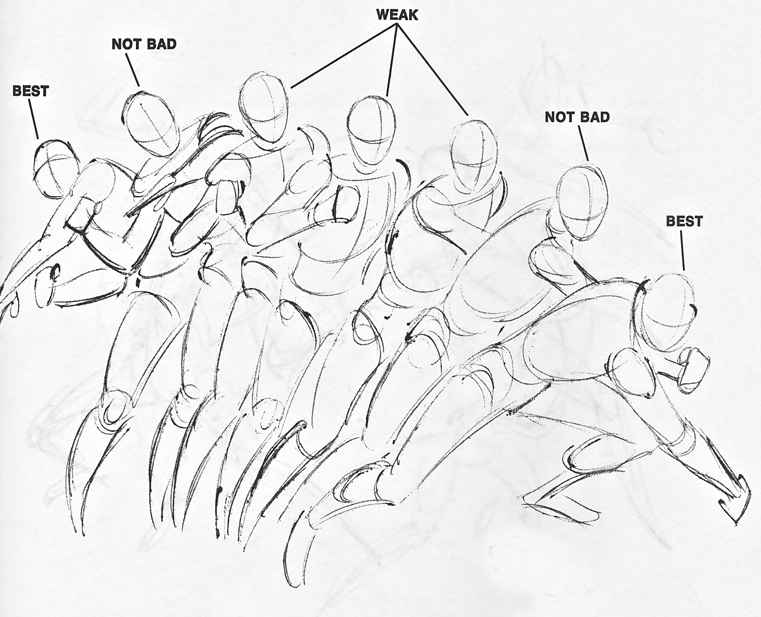

It’s a device much used by comic strip artists in order to create more dynamic compositions rather than choosing the less powerful, more static ‘in between’ frames. All of which makes for a more emotive piece of work.

How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way © Stan Lee and John Romita

Taslitzky’s life and politics were shaped by the turbulent events of the first half of the 20th Century. Born in Paris in 1911 to Russian emigres who fled the Russian revolution in 1905, his father died in the First World War. Taslitzky went on to study at the National School of Fine Arts in Paris. Politically active, he joined the Association of Revolutionary Writers and Artists and, later, the Communist Party. Around that time, he became involved with the French People's Front, producing placards for demonstrations. He also travelled to Spain in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War and exhibited alongside Picasso.

During the Second World War, Taslitzky became part of the French Resistance. Captured and imprisoned in 1941, he served time in prison before being deported to Buchenwald concentration camp as a political inmate and, during his time there, created more than 200 drawings detailing camp life. His mother, meanwhile, died in 1942 while being transported to Auschwitz.

After the war, as a member of the French Communist party, he created a number of works addressing contemporary political events, one of these was Riposte, depicting the dockers’ strike at Port de Bouc, near Marseilles, in 1949.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, France’s grip on its colonies began to slip, first in French Indochina, now Vietnam, when the Viet Minh, seeking independence, rebelled against French colonial control, and later in Algeria.

In solidarity with those claiming independence in Indochina, Communist union Dock workers in France refused to unload ships and load ships bound for Indochina, knowing that their cargoes of military and war materials would be used to suppress the uprisings. Between November 1949 to April 1950, the dock workers refusal to load ships bound for Indochina, or unload ships from America carrying weapons, spread until every French port apart from Cherbourg (where non-communist unions ran the docks) became involved. The government then sent in the CRS, the French riot police, to brutally break up the strikes and arrest the leaders. (The CRS can also be seen in action elsewhere in the exhibition, in Oliver Ressler’s films, Everything is Falling Apart; COP21 and The Zad).

French CRS - Everything’s Coming Together While Everything’s Falling Apart: COP21 / Oliver Ressler 2016

At the time, though, the strikes drew very little sympathy outside the working class. They were seen as ‘unpatriotic’ (where have we heard that before?), and in April 1950 the government passed laws against sabotage and refusal to transport arms. In the face of this, the strikes eventually petered out.

The history of the strikes, however, continued to be a political sore point for the French Government and Taslitzky’s painting attracted controversy when it was exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in 1951. It was removed by the police along with several other political works prior to a visit by France’s President, Vincent Auriol. It seems the culprit though was France’s Minister for the Arts, who just so happened to be the former governor of Port de Bouc.

Similarly, in 1953, social realist film-maker Paul Carpita met similar political stubbornness when he made a film, Le Rendez-vous des Quais, (A Meeting at the Docks) a love story set against the background of the same dock strikes. Carpita filmed in Marseilles port using guerrilla filming techniques; shooting on location without permission and, besides the lead actors (one of whom acted under a false name), using amateur actors drawn from the dock workers and local community itself. Under such conditions, the film took almost two years to complete, mixing fictional scenes and archive footage shot by Carpita during the strikes themselves.

Stills from Le Rendezvous de Quais directed by Paul Carpini

However, when it was finished, the film fell afoul of the same political sensitivities as Riposte. When Carpita attempted to show the film in Paris, it was seized by the CRS. The government immediately banned the film stating; “It retraces (which the synopsis does not state) a strike launched by the Dockers of Marseilles, under a union pretext, to take action against the Indochina war. It contains scenes of violent resistance to the public force. Its projection is likely to present a threat to public order.”

The film remained banned for 35 years until, by chance, it was found in the Archives du Film de Bois d'Arcy in 1988, when it was screened legally for the first time.

But the effects of the events depicted by Taslitzky continue to ripple on down through the years. In 2012, after Pussy Riot, the Russian feminist protest band, played the Moscow Cathedral, performing as part of an anti-Putin protest, three members Maria Alyokhina, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, and Yekaterina Samutsevich, were arrested and imprisoned. Their case attracted international attention. To help raise awareness of the case, English Pen published an anthology of poetry, Catechism: Poems for Pussy Riot, one of which, Propaganda, by Sandeep Parmar, was inspired by Taslitzky’s Riposte.

(l) The Bahri Yanbu © Benoit Tessier/ Reuters (r) Genoa dock protest © EPA

And again, today. On May 10th 2019, the Saudi Arabian cargo ship Bahri Yanbu arrived at Le Havre, France. There, dock workers, human rights activists and anti-war organisations prevented the ship from loading materiel headed for Yemen, where Saudi Arabia is currently waging a war. Unable to load the weapons, thanks to the dockers’ actions, the Bahri Yanbu continued onto Genoa, Italy.

However, forewarned by their French counterparts, the Italian dockers, who also had a history of refusing to load American ships during the Vietnam war, and again, during the Gulf War, also now refused to load suspected arms shipments bound for Yemen and the Bahri Yanbu was forced to leave port for Jeddah in Saudia Arabia without them.

It seems that the spirit of the French dock workers that Taslitzky captured 70 years ago is still alive and kicking today. Much like the punches thrown in Riposte, there is a through-line, a follow-through, from then to now, where the actions of those French dockers, as seen though the likes of Taslitzky, Carpita and Parmar and explored today by Ressler, remind us that solidarity and social conscience can still be a stinging riposte to power.